-

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a DNA virus with complicated genomic structures and has three types of genes that are under strict temporal expression. They are divided into immediate-early (α), immediate-early (β), and late (γ) genes (5). The α gene encode proteins that have essential functions in transcriptional activation and inhibition along with multiple regulatory and control processes of viral genes expressed at later times in infection (22). Meanwhile, as a result of interacting with host proteins (12), ICPs are most likely to control virus/cell interactions in terms of not only lytic infection, but also the establishment of viral latency in neuronal cells (19). It has been reported that the expression of some infected cell proteins (ICPs) in neuronal cells is apparently suppressed as a result of entry into HSV-1 viral latency (2). In contrast, a few studies have demonstrated that some ICPs expressed in neuronal cells did not activate the transcription of β and γ genes when regulated by factors within neuronal cells (25). No further investigations were conducted to verify either of these two hypotheses. It has been demonstrated that ICP0 and ICP22 might either activate or suppress transcription of viral genes at different phases via interactions with the transcri-ptional and regulatory systems (21). However, this interaction requires further confirmation in the neuronal cellular environment due to the specific biological properties of neuronal cells. As a consequence, a study was designed to investigate possible mechanisms in HSV-1 infected neuronal cells by characterizing neuroblastoma cells (1). This approach provides a novel approach in the study of this area. In cellular biology neuronal cells are end cells with specific functions, but lack a transcriptional and regulatory system for proliferation (24); unlike in other cells, this system has essential multifunctional structures, such as a promyelocytic leukaemia-nuclear body (PML-NB) etc. (3, 20), which has been shown to be associated with some ICP proteins in HSV-1 studies. All of these implications have provided evidence on the functions of HSV-1 ICPs in neuronal cells. More strikingly, the study of neuroblastoma cells prior to their proliferation has offered a potential model that requires further investigation. In this preliminary report, the expression, localization and possible potential interactive functions of HSV-1 ICP0, ICP22, and ICP27 in neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y strain) were investigated based upon the above evidence. The generated data are discussed.

HTML

-

Plasmids pEGFP-ICP22, pEGFP-ICP27, pGFP-ICP47, GEX-5X-1-PML, DNA3.1-PML expressing EGFP-ICP22, EGFP-ICP27, EGFP-ICP47 fusion proteins were constructed. pEFGP-N2 and pEFGP-C1 were purchased from Clontech company. pEGFP-ICP0 plasmid was donated by Dr. Roger D. Everett. All the recombinant plasmids were identified by enzyme digestion and sequencing.

Human neuroblastoma cell (SH-SY5Y strain) was maintained at 37℃ in F12 nutrient mixture with 10% bovine serum, 100μ/mL penicilline, 20μg/mL strep-tomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

-

Monolayers were grown to 70% confluence and transfected transiently by using Lipofectamine 2000. F12 nutrient mixture was replaced by serum free medium before transfection, in which plasmids DNA was diluted and mixed with Lipofectamine 2000 serum free medium and incubated at room tem-perature for 20 min. The DNA liposome complex was added to the cell culture and allowed to transfect after 6 hrs then a fresh media were added to the cell and allowed to indubate at 37℃.

-

The protein expressed by pGEX-5X-1-PML in E.Coli BL21 was purified and used to immunize mice at week 0, 2 and 5. Serum was prepared from blood collected 7 days after the last immunization and stored at-20℃.

-

Pre-cooled PBS (pH7.4) containing 2% poly-for-maldehyde was added to confluent cells and incubated at 4℃ for 15 min, and then maintained in ice acetone/methyl alcohol (7:3) for 5 min followed by blocking with 2% BSA, 0.5% Tween-20 and PBS (pH7.4) at 37℃ for 30 min. The primary antibody was bound to anti-PML serum at 37℃ for 90 min and secondary antibody was to sheep anti-mice IgG marked by TRITC at 37℃ for 30 min, with PBS washing for 3 times each in between. The complex was examined by immunofluroscence microscopy.

Cells and plasmids

Cell transfection

Antibody preparation

Immunofluorescence

-

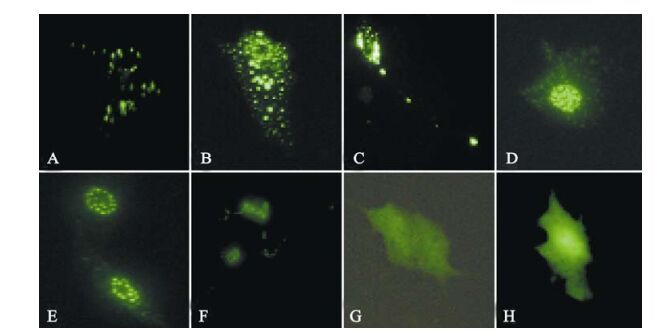

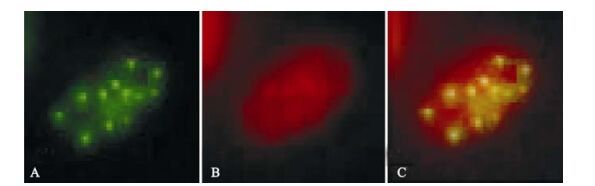

The ICP0 expression in transfected neuroblastoma cells started at 3 h post-transfection and continued for more than 120 h. Its was first observed in the cytoplasm and gradually migrated to the nucleus where it accumulated in ordered foci in the nucleus (Fig. 1). Comparison of these discrete structures with that of PML-NB, as detected with PML red immuno-fluorescence antibody, suggested that ICP0 is locali-zed on the PML-NB structure (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Fluorescence images of ICP0-EGFP in transfected SH-SY5Y cells. A-F: Expression of EGFP-ICP0 by SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pEGFP-ICP0 at 16 h, 22 h, 40 h, 66 h, 90 h and 186 h, respectively. G and H: Expression of GFP by SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pEGFP-N2 at 16 h and 186 h, respectively.

-

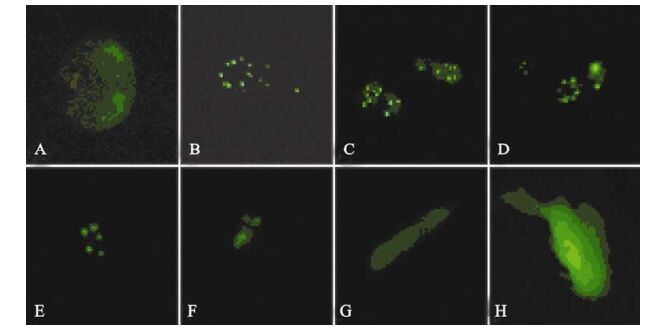

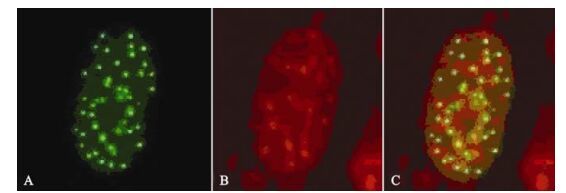

While expression of ICP22 started at 3 h post-transfection, it was transferred to the nucleus rather rapidly and remained there for more than 120 h (Fig. 3). As described in our previous studies, ICP22 localization to the nucleus is also characterized by ordered foci (20). At the same time, its localization in the nucleus is always associated with PML-NB-mediated nuclear structures. When ICP22-GFP fusion protein expression in cells was detected using anti-PML-NB immunofluorescence antibody, the spatial inter-association of ICP22 with PML-NB was clearly evident [Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Fluorescence images of ICP22-EGFP in transfected SH-SY5Y cells of different phase. A-F: Expression of EGFP-ICP22 by SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pEGFP-ICP22 at 16 h, 22 h, 40 h, 66 h, 90 h and 186 h, respectively. G and H: Expression of GFP by SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pEGFP-N2 at 16 h and 186 h earlier, respectively.

-

The ICP27 expression also started at 3 hrs post-trans-fection and lasted for over 120 h, during which time the protein was distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Fluorescence images of ICP27-EGFP in transfected SH-SY5Y cells of different phase. A-F: Expression of EGFP-ICP27 by SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pEGFP-ICP27 at 16 h, 22 h, 40 h, 66 h, 90 h and 186 h, respectively. G and H: Expression of GFP by SH-SY5Y cells transfected with pEGFP-N2 at 16 h and 186 h, respectively.

ICP0 expression in neuroblastoma cells

ICP22 expression in neuroblastoma cells

ICP27 expression in neuroblastoma cells

-

Numerous reports on the mechanisms of HSV-1 infection have been published (17), and most of them have focused on the relationship between the localization of ICP and its associated functions (23). This has resulted in the hypothesis that the localization of ICPs, particularly ICP0 and ICP22, which are associated with transcriptional and regula-tory functions in the nucleus, is associated with the PML-NB structure. This is because ICPs and the PML-NB structure display an obvious and clear co-localization (8) as well as many functional associa-tions (4). As a specific nuclear structure composed of many protein molecules and bound tightly to the nuclear matrix, PML-NB has many biological functions via associations with chromatin structures, including transcriptional and regulatory functions via modification processes including phosphorylation, SUMOylation, acetylation and deacetylation of different protein molecules (11). These processes have been characterized comprehensively by examining PML-NB binding to molecules with different functions, as well as specific functions occurring via the interaction of viral transcriptional and regulatory proteins with corresponding cellular systems (9). Nevertheless, as an important structure with prolife-rative characteristics, the existing type of PML-NB structure in neuronal cells remains unclear. Therefore, the association of its ICPs and PML-NB structure appears to be more significant for the establishment of specific latency of HSV-1 infection in neuronal cells.

As a multi-functional protein that transactivates HSV-1 early and late genes (6), ICP0 functions by interacting with other viral and cellular proteins (13). The fact that it is localized on the PML-NB structure implies potential transcriptional and regulatory functions. It has been demonstrated that ICP0 has effects on the ubiquitin and deacetylation systems via interactions on the PML-NB structure (10, 15), although this is most likely to result in the possibility of establishing an HSV-1 lytic infection when ICP0 exhibits its many functions. Furthermore, the co-localization of ICP0 and the PML-NB in neuro-blastoma cells with HSV-1 cytolytic infection further suggests that ICP0 activates viral gene transcription by interacting with PML-NB, which might influence the appearance of either cytolytic or latency because the host cellular environment of neuroblastoma cells maintains some of the basic characteristics of neuronal cells regardless of immortalization (16). Conse-quently, it can be ruled out that the transcriptional and regulatory systems in neuronal cells are the main factors influencing viral infectious types. This is further supported by the observed localization of ICP22 in neuroblastoma cells in the current study. Our results demonstrate that ICP22 nuclear localization in neuroblastoma cells is associated with PML-NB, which is consistent with its characteristics in other cells (18). On the other hand, the transcriptional and regulatory functions of ICP22 on HSV-1 late genes depend on the comprehensive function of associated cellular and viral molecules (14), as well as on the suppressive function of transcriptional activation of recently reported ICP22 on early genes and some cellular genes (7). This reveals that ICP22 functions by depending mostly on the transcriptional and regulatory systems, including the PML-NB. As a consequence, the localization and association of ICP22 PML-NB might contribute to the further investigation of possible mechanisms (18) establishing latency in cells resulting from transcription and suppression of ICP22. In addition, the observed ICP27 distribution in the nucleus and cytoplasm suggests that ICP27 is capable of transporting viral mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in cells with established cytolytic infection; unlike in other neuroblastoma cells exhibiting only ICP27 expression, ICP27 is distributed only in nucleus because there is no generation of viral mRNA. In a supplemental experiment (data not shown), the function of ICP0 and ICP22 were investigated in the contexts of CAT reporting system. The result suggested repressive and enhanced effects on viral transcription by ICP22 and ICP0 respectively. However, these experiments did not reflect a real process of viral infection in cells. Nevertheless, these results allowed us to hypothesize that infectious types of HSV-1 are most likely to depend on their trans-criptional and regulatory functions in infected cells.

In summary, our results and related analyses show that the function of HSV-1 ICPs on transcriptional and regulatory systems in host cells might contribute to determining HSV-1 infectious types, in particular the establishment of its latency in neuronal cells. Of course, such an assumption depends on the bioche-mical analysis of ICP0, ICP22, and ICP27 in neuro-blastoma cells and other available data, which require further studies. It is clear that more in depth inveti-gatons of HSV-1 infections of neuroblastoma cells and neuronal cells will have to be conducted.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: