-

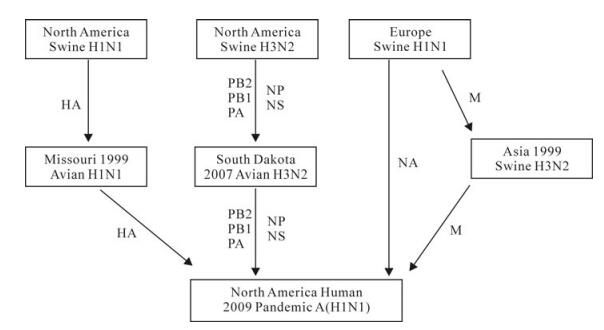

The worldwide spread of the 2009 "swine-origin" influenza A(H1N1) made World Health Organization formally declare a global pandemic (Stage 6) in June 2009[8]. According to the sequence data obtained from infected individuals, the pathogen is supposed to be the product of multiple reassortments containing genetic materials from previously isolated viruses circulating in humans, pigs and birds. Evolutionary studies indicated that this new virus probably originated from at least two swine influenza viruses circulating in different continents, with genomic segment 1 (PB2), 2 (PB1), 3 (PA), 4 (HA), 5 (NP), and 8 (NS) from North American virus and segment 6 (NA) and 7 (M) from Eurasian virus[1, 3, 5, 7]. Due to the big differences in nucleotide and amino acid sequences between the 2009 H1N1 viruses and the previously isolated strains, the immediate ancestors are still elusive and a lucid evolutionary track of the emerging virus remains far from reach.

A better understanding of the influenza virus evolution and reassortment history is critical for developing efficient preventive strategy against future emerging influenza viruses, especially for the highly pathogenic strains, like H5N1, which could be a lethal pathogen of the next pandemic. In order to understand the evolution of the 2009 H1N1 virus, we regularly searched the influenza virus sequence database in GenBank for emerging clues. To our surprise, our online blast analysis showed that, for all the six genomic segments originated from North America, all best blast hits contained avian strains. This prompted us to consider birds as the intermediate carriers of the 2009 H1N1 virus. Since birds have the ability to migrate long distances, it is plausible that birds caused one or more of the inter-continental reassortments. To test this hypothesis, we studied the GenBank for similar strains in North American avian strains and found that all the six North American segments had already established in North American bird populations before the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. Phylogenic analysis also indicated that these avian viruses could play a role in the evolution of the 2009 H1N1 virus.

HTML

-

The sequences of the first nearly complete genome of the newly emerging influenza virus (A/California/ 04/2009(H1N1)) were submitted by the United States CDC to GenBank on April 27, 2009 with accession number FJ966079 through FJ966086 representing segment 1 through segment 8 which range from 2280bp to 838bp in size respectively. We performed blast analysis against GenBank database"nr" on the website of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with the online nucleotide blast program BLASTN[9]. The eight segments of the 2009 pandemic strain A/Califolia/04/ 2009 (H1N1) were individually analyzed with default parameters and targets for each query were retrieved. Of the retrieved targets, the newly submitted 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) viruses were excluded.

-

The influenza virus strains used in this analysis were copied from a previous publication[1] and represent different lineages. The alignment was conducted by Clustal W and the trees were generated by MEGA4 software using neighbor-joining method rooted on the South Dakota avian strains.

Blast analysis

Phylogenic analysis

-

The new pandemic aroused enormous interests in the studies of influenza and surveillance of influenza in human and in other animals has since been greatly improved. Large numbers of influenza virus sequence data have been deposited into public sequence databases since the identification of 2009 H1N1 virus. To find if the recently published influenza sequence contains any new information which could help to reveal the route of the evolution of the 2009 H1N1 virus, we searched the GenBank sequence database every a few weeks. Our search demonstrated that some sequences recently submitted to GenBank showed better sequence similarities with 2009 H1N1 virus than any of the sequences submitted before the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. We unexpectedly found that, for all the six genetic segments of 2009 H1N1 virus originated from North America (PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, and NS), all the top blast hits are North American birds. Specifically, four North American water bird strains, namely A/pintail/SD/Sg-00126/2007, A/ mallard/ SD/Sg-00128/2007, A/mallard/SD/Sg-00127/ 2007, and A/mallard/SD/Sg-00125/2007, exhibited the best identities with the 2009 H1N1 virus for five of the six genome segments (PB2, PB1, PA, NP, and NS), and for the other segment HA, A/Turkey/MO/ 24093/99 was the best blast match. Table 1 lists the top 10 hits of the blast analysis performed with the six genomic segments of the 2009 pandemic strain A/ Califolia/ 04/2009 (H1N1) (The analysis was conducted on NCBI website http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/ on Jan 21, 2010. For detailed blast results, see the supplementary material excel table). All these South Dakota strains are of H3N2 subtype and were collected in September 2007 in South Dakota [4] while the Missouri turkey strain is of H1N1 subtype [6]. The South Dakota strain sequences are closely related to each other as well as to some other previously isolated turkey and duck strains from North America (for example: A/turkey/Ohio/313053/04(H3N2), A/turkey/ Ontario/31232/2005(H3N2), A/duck/NC/91347/01(H1N2), (see Table 2). These results demonstrated that these avian viruses circulating in North American birds contain the genetic materials most closely related with the 2009 H1N1 virus. The top hits of the 2009 H1N1 virus genetic segments distributed in different kinds of birds in different regions in North America indicated that these highly homologous gene segments have already established in the North American avian population. Since these South Dakota avian viruses simultaneously contain five of the six closest segments of the 2009 pandemic virus originated in North America, it strongly suggests that these South Dakota duck viruses isolated in 2007 are the closest known relatives of the 2009 pandemic strains.

Table 1. Top 10 hits of the blast analysis performed with genes of the 2009 pandemic strain A/Califolia/04/ 2009 (H1N1) ranked by identity score

Table 2. The top hits of the blast analysis performed with genes of A/mallard/South Dakota/Sg-00128/2007, showing previously isolated North American avian strains

-

In order to explore the evolutionary relationship of these North American avian strains and the 2009 H1N1 strains, phylogenic trees of the five segments were generated with MEGA4 software (Fig. 1-5). All the strains used in the publication[1]were included to ensure proper strain coverage and representation. The avian strains list in Table 1 and Table 2 are also included in the phylogenic trees to show the relationship of 2009 H1N1 viruses and the avian viruses (figures not shown, see reference[1]). These phylogenic trees showed that, for all the five segments, the 2009 H1N1 strains clustered with both North American swine strains and North American avian strains. The long branch length of the 2009 S-OIV to the other strains indicates that the ancestor strain of the 2009 s-OIV is still out of reach to us.

Figure 1. Putative sources of the 2009 pandemic influenza virus A (H1N1). The eight genome segments of the 2009 pandemic influenza virus came from different sources via various routes. The majority segments (PB2, PB1, PA, NP, and NS) came from the North American triple reassortant swine virus subtype H3N2, and entered South Dakota ducks in 2007. The HA gene was from the North American classic influenza virus and enter North American birds in 1999. The NA gene was derived from European swine influenza virus. The M gene segment was from the European swine too, and had been circulating in Asian swine population before entering the 2009 pandemic strain.

-

The above observation that the North American avian viruses are among the closest strains surveiled so far prompts us to propose that these strains could be involved in the evolution of the 2009 H1N1 virus. There are two other evidences to support hypothesis. The first evidence is that birds are capable of long-distance migration. It is believed that the 2009 H1N1 viruses was the result of multiple reassortment with genetic segment of human origin (PB1), avian origin (PB2 and PA) and swine origin (HA, NP, NA, M, and NS) from North America (PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, and NS), Eurasia (NA and M) [1, 2, 5]. The long-distance migration capacity makes wild birds the best candidates to carry the influenza viruses across the continents to provide the chance for the inter-continent reassortments. Even within a local region, birds are preferable host to bring about reassortment due to its mobility. Secondly birds are the biggest reservoir of influenza viruses. Many influenza viruses cause only mild disease or are asymptomatic in birds and thus it is sometime difficult to conduct influenza surveillance in wild birds. If the birds are intermediate ancestors of the 2009 H1N1 virus, it may explain why the evolution of the 2009 H1N1 virus is still obscure. A possible reassortment history of 2009 H1N1 virus might be: reassortments occurred among the avian strains, like South Dakota waterfowl strains (contributing PB2, PB1, PA, NP, and NS) and the Missouri turkey strain A/Turkey/MO/24093/99 (H1N2) (contributing HA), and the resulting strains either enter the North American swine strains or cross the ocean and enter the Eurasian swine strains in succeeding reassortment incidents (Fig. 1).

Nevertheless, there is also another possibility, that is, these North American avian strains are not the ancestors but just the siblings of the 2009 H1N1 viruses. In this situation these North American avian strains and 2009 H1N1 viruses have common ancestors and one branch of the ancestors entered and established in the bird populations and another one remained in the swine population which eventually evolved into the 2009 H1N1 viruses after accumulating point mutations and reassortments. No matter the North American avian strains are the ancestors or just the siblings of the 2009 H1N1 viruses; it is convinced that they are evolutionally closely related. Their close relationship implies that there is a good chance to trace the evolutionary history of the 2009 H1N1 around these birds. So enhanced influenza sur-veillance in North American bird population and related animals will probably reveal the evolutionary route of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) viruses.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: