-

Dear Editor,

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus(MERS-CoV)has affected over 1600 people across four continents; it has a fatality rate of about 36%(WHO, 2015). Approximately 75% of MERS-CoV patients have a pre-existing medical condition(Zumla et al., 2015). MERS-CoV is especially severe in patients with comorbidities.

Several studies have identified the risk factors for mortality in patients with MERS-CoV: presence of respiratory disease, age over 60 years, concomitant infections, and hypoalbuminaemia increase the mortality risk. About 60% of the individuals with 'at risk' conditions succumb to death(Banik et al., 2015).

However, these studies were relatively small and the risk factors for disease severity were rarely explored(Majumdar et al., 2015; Korea CDC, 2015; Saad et al., 2014). To this end, we have explored the key risk factors for mortality and severity of MERS-CoV from a larger dataset of Saudi Arabian patients.

Data for this analysis were obtained from the Comm and and Control Center(CCC)of Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health(MoH). This center has been publicly reporting the MERS-CoV cases in Saudi Arabia since May 2013 on their website(http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/CCC/PressReleases/Pages/default.aspx). The site contains data on > 80% of the Saudi Arabian MERS cases. Initially, only limited information such as patients' age, sex, nationality, address, date of diagnosis, presenting symptoms, and presence of any pre-existing condition were made publicly available; however, since 24th September 2014, additional information on likely exposure to animals and other suspected MERS cases were added, and it was recorded whether the exposure likely occurred at health care settings or in community settings.

Two authors(ASA and GRB)extracted the data from the Saudi MoH website and added it into a data extraction spread sheet; the first author(GRB)double checked the entries, any disagreement was resolved through verifying and ensuring data integrity. The following data were abstracted in the extraction sheet: date of confirmation of the diagnosis, age and sex of the patient, nationality, city or region of the patient's residence, symptoms, whether the patient required intensive care unit(ICU)admission, status of the patient at the time of data entry(recovered, being cared in the hospital or ICU, or died) and whether the patient was a health care worker(HCW). It was also noted if the patient had any pre-existing medical condition and, if so, what those medical conditions were. Additional information(e.g., history of exposure to animal or contact with suspected cases in health care and /or community settings)were collated in a separate column irrespective of whether or not the information was used in this analysis.

The proportion of patients with a particular risk factor, such as pre-existing illness or age ≥ 65 years, was calculated separately for those who died and for those who survived. For this analysis, a case of MERS was considered 'severe' if he/she needed admission to ICU at any time point during the course of the illness, all other cases were considered 'not severe', irrespective of wheth-er they required hospitalization or not. The proportion of patients with a particular risk factor such as the presence of a named pre-existing medical condition was calculated separately for 'severe' and 'not severe' cases. Odds ratios(ORs)for mortality and severity in the presence of a potential risk factor were calculated with 95% confidence interval(95%CI)by using an authentic online calculator(http://vassarstats.net/odds2x2.html). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

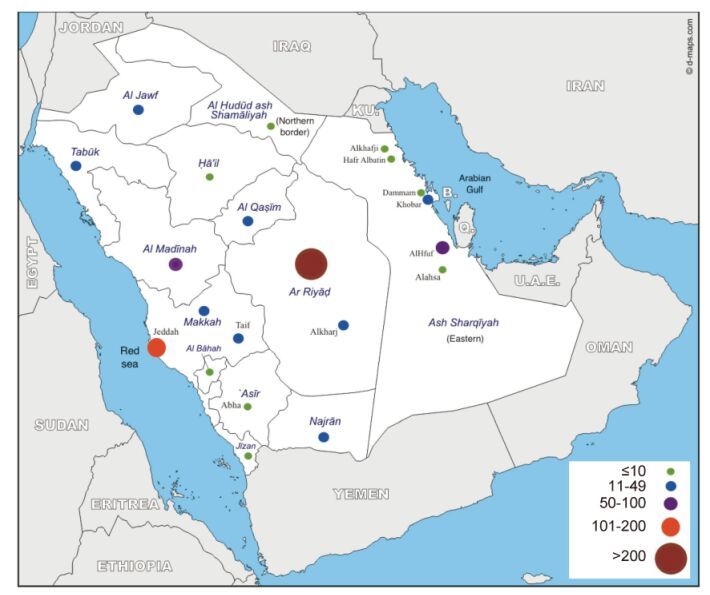

As of 11 October 2015, data on 1060 MERS-CoV cases aged 9 months to 109 years(median 52 years)were published in the Saudi MoH website; 65% were male(M/F ratio: 1.5). Among them, 81%(846/1049)were Saudi residents; the non-Saudis(19%, 203/1049)included expatriates and immigrants mainly from the Philippines, Palestine, Pakistan, and Egypt. Riyadh had the highest number of cases(45.5%, 482/1058), followed by Jeddah(18%, 192/1058)(Figure 1). One hundred and forty one(14%)of all MERS cases were HCWs. Of 379 patients for whom such data were available, 84(22%)had a history of exposure to health care settings, and of 595 patients for whom such data were available, 250(42%)gave a history of exposure to suspected cases in the community. Of 350 patients for whom the data were available, 17%(60)gave a history of exposure to animals: 3% to camels and 14% to other unspecified animals.

The presence or absence of a co-morbidity was recorded in two-thirds of cases(n = 685); of these, 496(72.4%)were considered as being at risk, either because they were aged ≥ 65 years or had one or more pre-existing medical conditions. Of 496, 208(41.9%)were aged 65 years or older, and apart from seven(3%), all had pre-existing medical conditions; in 108(22%)cases, the conditions were specified: diabetes mellitus(50%, 54/108), hypertension(45%, 49/108), and renal(30%, 32/108), cardiac(19%, 21/108), pulmonary(17%, 18/108), malignant(13%, 14/108), and neurological diseases(5%, 5/108). Another 16%(17/108)had other chronic diseases in various combinations. Over half(52%)of the patients had multiple comorbidities.

Of the total 1060 cases, 384(36%)died by the time the data were analyzed, of which 270(70%)were male. Diabetes, hypertension, renal disease, malignancy, and several other conditions hitherto termed as miscellaneous conditions(e.g., anemia, obesity and congenital abnormalities, diseases of the liver and gall bladder, or steroid use)were significant risk factors for mortality from MERS-CoV(Table 1). Male sex was also a significant risk factor for mortality but the proportions of diabetes, hypertension, renal disease, malignancy, and miscellaneous conditions in men were not significantly different from that in women.

Risk factors Died n (%)N = 260 Survived n (%)N = 428 OR* (95% CI)** P value Diabetes 33 (12.7) 21 (4.9) 2.8(1.6–5) < 0.01 Hypertension 26(10) 22(5.1) 2.1(1.1–3.7) 0.02 Kidney disease 22 (8.5) 10 (2.3) 3.9 (1.8–8.3) < 0.01 Heart disease 11 (4.2) 9 (2.1) 2.1 (0.8–5) 0.11 Malignant disease 11 (4.2) 2 (0.5) 9.4 (2.1–42.8) < 0.01 Lung disease 8 (3.1) 8 (1.9) 1.7 (0.6–4.5) 0.31 Neurological condition 3 (1.2) 2 (0.5) 2.5 (0.4–15) 0.37 Miscellaneous condition 13 (5) 4 (0.9) 5.6 (1.8–17.3) < 0.01 Male sex 194 (74.6) 270 (63.1) 1.7 (1.1–2.6) 0.03 Notes: * OR, odds ratio; **95%CI, 95% confidence interval. Bold values denote significant difference. Table 1. Risk factors for mortality of MERS patients.

Of 676 MERS patients who survived, 130(19.2%)required ICU admission, therefore were considered to have a severe form of the disease. Of those who survived, 428(63%)had pre-existing conditions, of which diabetes and neurological conditions were significant risk factors for severity(Table 2).

Conditions Severe n (%)N = 130 Not severe n (%)N = 298 OR* (95% CI)** P value Diabetes 11(8.5) 10 (3.4) 2.7 (1.1–6.4) 0.02 Hypertension 10 (7.7) 12 (4) 2 (0.8–4.5) 0.11 Kidney disease 3 (2.3) 7 (2.3) 1 (0.2–3.8) 0.98 Neurological condition 2 (1.5) 0 (0) NaN 0.03 Lung disease 2 (1.5) 6 (2) 0.8 (0.2–3.8) 0.74 Malignant disease 1 (0.8) 1(0.3) 2.3 (0.1–37.1) 0.55 Heart disease 2(1.5) 7 (2.3) 0.6 (0.1–3.2) 0.59 Miscellaneous condition 2 (1.5) 3 (1) 1.5 (0.3–9.3) 0.64 Male sex 83 (63.8) 187 (62.8) 1.1 (0.7–1.6) 0.82 Notes: *OR, odds ratio; **95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NaN, Not a Number. Bold values denote significant difference. Table 2. Risk factors for severity of MERS patients.

These results corroborate the findings of other smaller studies from Saudi Arabia and South Korea that showed that older age and presence of co-morbid conditions were associated with higher mortality(Saad et al., 2014; Feikin et al., 2015; Majumder et al., 2015; Korea CDC, 2015). Our study has specifically identified that diabetes, hypertension, renal disease, malignancy, miscellaneous conditions, and male sex were the main risk factors for mortality. Another small study also demonstrated that diabetes was significantly associated with mortality(OR=15.7; 95%CI 2.5-100.7)(Shalhoub et al., 2015). In contrast, among South Korean patients, underlying respiratory disease and older age were the key risk factors for mortality(Korea CDC, 2015). In our study, presence of a respiratory disease was not a significant risk factor and we did not explore the association of older age with mortality, because essentially all patients aged ≥ 65 years in our cohort had a pre-existing disease, but age itself could be an independent risk factor, as other studies from Saudi Arabia and South Korea demonstrated that age > 60 years(in some studies ≥ 65 years)was significantly associated with mortality(Feikin et al., 2015; Majumder et al., 2015; Saad et al., 2014). Additionally, Majumder et al., (2015) demonstrated that for every one year of increase in age, the odds of fatality increased by 12%(OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.1-1.2). The risk factors might vary geographically; additionally, the relatively small sample sizes in other studies could have missed other significant risk factors.

Our study also demonstrates that men had higher odds of dying from MERS-CoV, which is unsurprising given the fact that the disease predominantly affects men. Another Saudi study also demonstrated that the case fatality rate was higher for men(52%)than for women(23%)(Alghamdi et al., 2014). In the South Korean cohort, even though being male increased the odds of mortality, the association was not significant(Majumder et al., 2015), likely because of small size. In our cohort, 65% of the patients were men, while in some other series, 97% of the cases were men, which is explained by the fact that men more often come in close contact with camels than women in Arabian countries(Alraddadi et al., 2015).

MERS-CoV patients with diabetes and neurological conditions were more likely to require ICU admission than those without these conditions, which are unique findings. In contrast, a study involving 70 Saudi Arabian MERS patients showed that concomitant infections(OR 14.1, 95% CI 1.6-126.1, P = 0.02) and low albumin levels(OR 6.3, 95% CI 1.2-31.9; P = 0.03)were independent risk factors for ICU admission(Saad et al. 2014). Approximately 14% of the MERS-CoV patients in our cohort were HCWs, and exposure to healthcare setting was an important ground for transmission of the virus(over 20%), which is supported by other available data(Oboho et al., 2015; Petersen et al., 2014; Saad et al., 2014), and mathematical modelling suggests that nosocomial transmission is over four times higher than community transmission(Chowell et al., 2014).

Considering that pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, renal, malignant, neurological, and miscellaneous conditions are risk factors for severe outcomes of MERS-CoV, due attention should be paid to optimum control of these conditions. Co-infection with MERS-CoV and influenza plus other bacterial and viral infections have been reported(Zumla et al., 2015), and co-infection is seen to increase the severity of the disease(Saad et al., 2014). Therefore, vaccinations against influenza and pneumococcal disease should be considered for the high-risk individuals(those with pre-existing disease and /or aged ≥ 65 years). These vaccines could prevent co-infections by influenza and Streptococcus pneumoniae as well as the fatal outcomes of MERS-CoV. They may even reduce the need for hospital visits or even ICU admission.

The limitations of this study are: data could not be validated from the original source and multivariate analysis was not considered. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable information on risk factors for severity and mortality in MERS patients from a relatively large dataset, and has actually ascertained some key risk factors. We hope this study would inspire further research based on even larger datasets.

HTML

-

RB declares grants, personal fees, and other from Baxter, CSL, GlaxoSmithKlein, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Romark, and Sanofi Pasteur for the conduct of sponsored research, travel to conferences, or consultancy work, all outside the submitted work and directed to research accounts at The Children's Hospital at Westmead, NSW, Australia. HR declares personal fees from Pfizer for consulting or serving on an advisory board, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: