HTML

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARSCoV) is the causative agent of the 2002-2003 SARS pandemic, which resulted in more than 8000 human infections worldwide and an approximately 10% fatality rate (Ksiazek et al. 2003; Peiris et al. 2004). The virus infects both upper airway and alveolar epithelial cells, resulting in mild to severe lung injury in humans (Peiris et al. 2003).

During the SARS outbreak investigation, epidemiological evidence of a zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV was identified (Xu et al. 2004). Isolation of SARS-related coronavirus (SARSr-CoVs) from masked palm civets and the detection of SARS-CoV infection in humans working at wet markets where civets were sold suggested that masked palm civets could serve as a source of human infection (Guan et al. 2003). Subsequent work identified genetically diverse SARSr-CoVs in Chinese horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus sinicus) in a county of Yunnan Province, China and provided strong evidence that bats are the natural reservoir of SARS-CoV (Ge et al. 2013; Li et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2016). Since then, diverse SARS-related coronaviruses (SARSr-CoVs) have been detected and reported in bats in different regions globally (Hu et al. 2015). Importantly, SARSr-CoVs that use the SARS-CoV receptor, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) have been isolated (Ge et al. 2013). These results indicate that some SARSr-CoVs may have high potential to infect human cells, without the necessity for an intermediate host. However, to date, no evidence of direct transmission of SARSr-CoVs from bats to people has been reported.

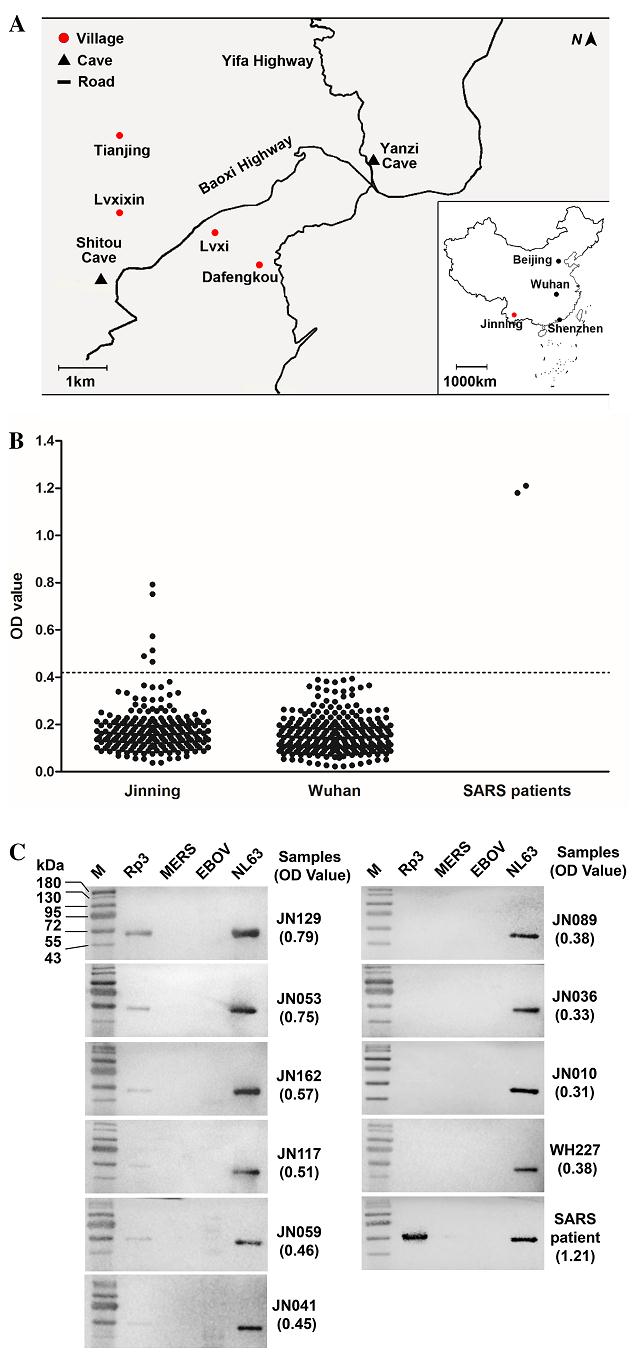

In this study, we performed serological surveillance on people who live in close proximity to caves where bats that carry diverse SARSr-CoVs roost. In October 2015, we collected serum samples from 218 residents in four villages in Jinning County, Yunnan province, China (Fig. 1A), located 1.1-6.0 km from two caves (Yanzi and Shitou). We have been conducting longitudinal molecular surveillance of bats for CoVs in these caves since 2011 and have found that they are inhabited by large numbers of bats including Rhinolophus spp., a major reservoir of SARSr-CoVs. This region was not involved in the 2002-2003 SARS outbreaks and none of the subjects exhibited any evident respiratory illness during sampling. Among those sampled, 139 are female and 79 male, and the median age is 48 (range 12-80). Occupational data were obtained for 208 (95.4%) participants: 85.3% farmers and 8.7% students. Most (81.2%) kept or owned livestock or pets, and the majority (97.2%) had a history of exposure to or contact with livestock or wild animals. Importantly, 20 (9.1%) participants witnessed bats flying close to their houses, and one had handled a bat corpse. As a control, we also collected 240 serum samples from random blood donors in 2015 in Wuhan, Hubei Province more than 1000 km away from Jinning (Fig. 1A) and where inhabitants have a much lower likelihood of contact with bats due to its urban setting. None of the donors had knowledge of prior SARS infection or known contact with SARS patients.

Figure 1. SARSr-CoV serosurveillance. (A) Map of Xiyang town, Jinning County, Yunnan Province, China. Shown here is the location of the 4 villages (Tianjing, Dafengkou, Lvxi, Lvxixin) around 2 bat caves (Yanzi Cave and Shitou Cave) chosen for this study. The map of China is also shown in the inset indicating the location of Wuhan, where the negative control sera were collected, in relation to Jinning, Shenzhen and the capital Beijing. Serological reactivity of serum samples with recombinant SARSr-CoV NP protein. B ELISA test. The dotted line represents the cutoff of the test. C Western blot analysis. Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kDa.

His-tagged nucleocapsid protein (NP) of the following viruses were expressed and purified in E. coli for this study: SARSr-CoV Rp3; human coronaviruses (HCoVs) HKU1, OC43, 229E, NL63; Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV); and Ebola virus (EBOV). In addition, the receptor binding domains (RBD) of the spike protein (S) from SARS-CoV, bat SARSr-CoVs Rp3, WIV1, and SHC014 were produced in mammalian cells (Ge et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2016).

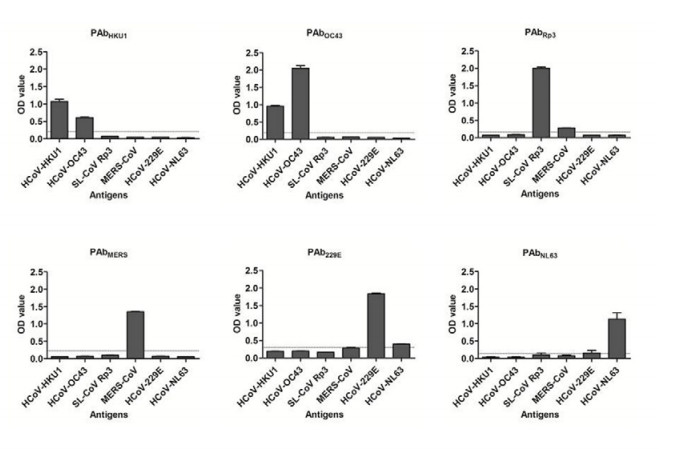

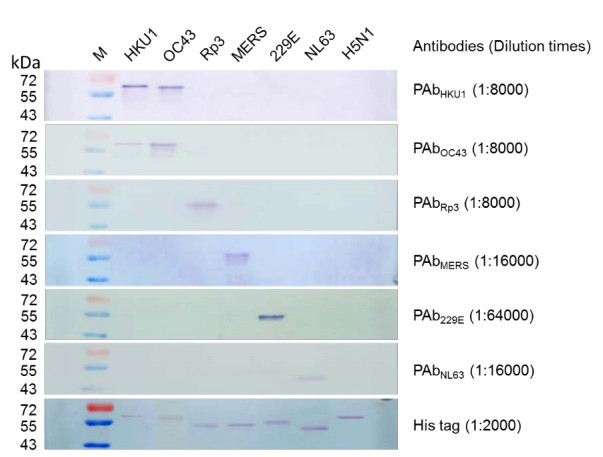

Polyclonal antibodies against each of the six NPs were prepared in rabbits as previously published (He et al. 2006). Cross-activity was evaluated with ELISA and Western blot (Supplementary Figures S1, S2). No significant cross-activity was detected among NPs and their corresponding antibodies for Rp3, MERS-CoV, NL63, or 229E. Cross-reaction was detected between OC43 and HKU1 as reported previously (Lehmann et al. 2008).

The Rp3 NP was chosen to develop a SARSr-CoV specific ELISA for serosurveillance. Micro-titer plates were coated with 100 ng/well of recombinant Rp3 NP and incubated with human sera in duplicates at a dilution of 1:20, followed by detection with HRP labeled goat antihuman IgG antibodies (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) at a dilution of 1:20, 000. The 240 random serum samples collected in Wuhan and two SARS positive samples from Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University (kindly provided by Prof. Xiaoyan Che)1 were used to set a cutoff value. We used the mean OD value of the 240 samples plus three standard deviations to set the cutoff value at 0.41. A total of six positive samples were detected by ELISA (Fig. 1B). The specificity of these positive samples was confirmed by Western blot with recombinant Rp3 NP (Fig. 1C) together with NP of NL63, MERS-CoV and EBOV. The degree of reactivity in Western blot correlated well with the ELISA OD readings, providing further confidence in the ELISA screening method. None of the sera reacted with NPs of either MERS-CoV or EBOV. On the other hand, all 10 human sera (9 from Jinning and 1 from Wuhan), regardless of their Rp3 NP reactivity, reacted strongly with the NL63 NP as expected due to high prevalence of NL63 infection in humans worldwide (Abdul-Rasool and Fielding 2010).

We conducted a virus neutralization test for the six positive samples targeting two SARSr-CoVs, WIV1 and WIV16 (Ge et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2016). None of them were able to neutralize either virus. These sera also failed to react by Western blot with any of the recombinant RBD proteins from SARS-CoV or the three bat SARSr-CoVs Rp3, WIV1, and SHC014. We also performed viral nucleic acid detection in oral and fecal swabs and blood cells, and none of these were positive.

The demography and travel histories of the six positive individuals (four male, two female) are as follows. Two males (JN162, 45 years old, JN129, 51 years old) are from the Dafengkou village; two males (JN117, 49 years old, JN059, 57 years old) from Lvxi village; and two females (JN053, JN041, both 55 years old), from Tianjing village. In the 12 months prior to the sampling date, JN041 was the only individual who travelled outside of Yunnan, to Shenzhen, a city 1400 km away from her home village (Fig. 1A). JN053 and JN059 had travelled to another county 1.4 km away from their village. JN162 had travelled to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan, 63 km away. JN129 and JN117 had never left the village. It is worth noting that all of them had observed bats flying in their villages.

Our study provides the first serological evidence of likely human infection by bat SARSr-CoVs or, potentially, related viruses. The lack of prior exposure to SARS patients by the people surveyed, their lack of prior travel to areas heavily affected by SARS during the outbreak, and the rapid decline of detectable antibodies to SARS-CoV in recovered patients within 2-3 years after infection strongly suggests that positive serology obtained in this study is not due to prior infection with SARS-CoV (Wu et al. 2007). The 2.7% seropositivity for the high risk group of residents living in close proximity to bat colonies suggests that spillover is a relatively rare event, however this depends on how long antibodies persist in people, since other individuals may have been exposed and antibodies waned. During questioning, none of the 6 seropositive subjects could recall any clinical symptoms in the past 12 months, suggesting that their bat SARSr-CoV infection either occurred before the time of sampling, or that infections were subclinical or caused only mild symptoms. Our previous work based on cellular and humanized mouse infection studies suggest that these viruses are less virulent than SARS-CoV (Ge et al. 2013; Menachery et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2016). Masked palm civets appeared to play a role as intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV in the 2002-2003 outbreak (Guan et al. 2003). However, considering that these individuals have a high chance of direct exposure to bat secretion in their villages, this study further supports the notion that some bat SARSr-CoVs are able to directly infect humans without intermediate hosts, as suggested by receptor entry and animal infection studies (Menachery et al. 2016).

The failure of these NP ELISA positive sera to either neutralize live virus or react with RBD proteins in Western blot could be explained by at least two hypotheses. First, the immune response to the bat SARSr-CoV S protein may be weaker than that to the NP protein or may wane more rapidly, especially in subclinical infections, resulting in antibody levels is too low to be detected by our assays. Secondly, other bat SARSr-CoV variants may be circulating in bats in these villages that have highly divergent S proteins and have not yet been detected in our surveillance studies.

Coronaviruses are known to have a high mutation rate during replication and are prone to recombination if different viruses infect the same individual (Knipe et al. 2013). From our previous studies of bat SARSr-CoVs in the two caves near these villages, we have found genetically highly diverse bat SARSr-CoVs and evidence of frequent coinfection of two or more different SARSr-CoVs in the same bat (Ge et al. 2013). Our current study suggests that our surveillance is not exhaustive, as one would have expected, and that further, more extensive surveillance in this region is warranted. It might also be prudent to combine serological surveillance with molecular surveillance of bats in future, despite the technological challenges that this represents.

-

This study was jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (81290341) to ZLS; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (Award Number R01AI110964) to PD and ZLS, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT project Grant (Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-14-00102) to PD; and Singapore NRFCRP Grant (NRF2012NRF-CRP001-056) and CD-PHRG Grant (CDPHRG/0006/2014) to LFW.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

This study was approved by the Wuhan Institute of Virology Institutional Review Board (China) and by Hummingbird IRB (USA).

Conflict of interest

Animal and Human Rights

-

Figure S1. Two-way cross-reaction ELISA testing between 6 coronavirus NPs and their corresponding rabbit polyclonal antibodies. The NP proteins (100 ng/well) were coated in 96-well micro-plate and tested with polyclonal antibody against NPs of SARS-related CoV Rp3 (PAbRp3), HCoV HKU1 (PAbHKU1), HCoV OC43 (PAbOC43), MERS-CoV (PAbMERS), HCoV229E (PAb229E) and HCoV NL63 (PAbNL63), respectively. The serum was diluted at 1:16, 000 or 1:64, 000 (for PAb229E and PAbNL63). HRP labeled goat antirabbit IgG (1:20, 000) was used as secondary antibody and detected with TMB substrate. The horizontal line in the diagram indicates cutoff value determined from negative rabbit sera collected before immunization.

Figure S2. Two-way cross-reaction Western blotting between 6 coronavirus NPs and their corresponding rabbit polyclonal antibodies. The NP proteins (100 ng) were run on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The membrane was incubated with the different rabbit sera at different dilutions indicated on the right (in brackets). Goat antirabbit IgG conjugated with AP (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) were used for detection at a dilution of 1:2000. Influenza virus H5N1 NP was used as negative control. Numbers at the left are molecular masses (in kilodaltons)

1 Prof. Xiaoyan Che—deceased

DownLoad:

DownLoad: