HTML

-

Heparan sulfate (HS) is a highly sulfated polysaccharide composed of up to 100 repeating uronic acid (D-glucuronic acid [GlcA] or L-iduronic acid [IdoA]) and D-glucosamine (GlcN) disaccharide units. HS is ubiquitously expressed on the cell surface and extracellular matrix of almost all cell types as heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) (17, 45, 63). HSPGs are composed of HS polysaccharide side chains covalently linked to a protein core via a tetrasac-charide linker region. HS plays a role in multiple biological processes including blood coagulation, lipid metabolism, regulation of embryonic development, neurogenesis, angiogenesis, axon guidance, growth factor and cytokine interactions, and HS can serve as a receptor for many viruses and bacteria (17, 37, 45, 63, 91). The functional diversity of HS is due to extensive modifications HS undergoes during its biosynthesis.

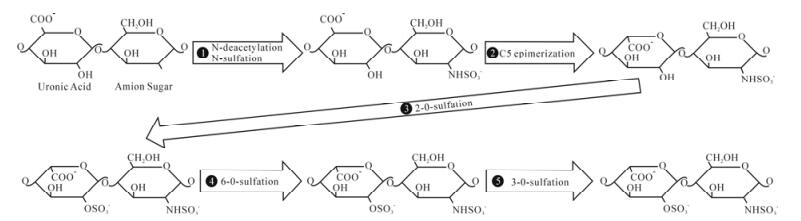

The biosynthesis of HS is a sequential, multi-step process that occurs in the Golgi apparatus. Synthesis of HS begins with the assembly of the tetrasaccharide linker region (GlcA-Gal-Gal-Xyl) on serine residues of the protein core (17, 45, 63). After the initial addition of an N-acetylated glucosamine (GlcNAc) residue to begin the HS chain, polymerization occurs by the addition of alternating GlcA and GlcNAc residues. As polymerization occurs, HS undergoes a series of modifications. The enzymes involved include glycosyltransferases, an epimerase, and sulfotrans-ferases. First, N-deacetylation and N-sulfation of GlcNAc occurs, converting it to N-sulfoglucosamine (GlcNS). Next is the C5 epimerization of GlcA to IdoA. The next modification steps involve O-sulfation by either 2-O-sulfotransferases, 6-O-sulfotransferases, or 3-O-sulfotransferases. First is 2-O-sulfation of IdoA and GlcA, followed by 6-O-sulfation of GlcNAc and GlcNS units, and finally 3-O-sulfation of GlcN residues (17, 45, 63). The arrangement of these modified residues creates distinct binding motifs on the HS chain that are believed to regulate its functional specificity and allow HS to function in distinct biological processes including viral membrane fusion and penetration (66).

-

The abundant expression of HS on the surface of almost all cell types makes it an ideal receptor for viral infection. In addition, the negativecharge of the highly sulfated HS makes it well suited to interact with viral proteins carrying positive charges (81). Evidence also suggests that virus can bind specifically to HS by interacting with specific saccharide sequences (66). This suggests a relationship between HS structure and viral activity. The structural specificity shown by viral infection could be critical for understanding viral activity. HS serves as a receptor for an array of viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis-C, human papillomavirus, and Dengue virus (5, 10, 29, 83). In addition, virtually all human herpesviruses, with the possible exception of Epstein Barr virus (EBV), use HS as an initial co-receptor for entry (67). Among the herpesviruses, interaction of HS with herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) has been most studied and therefore, it forms the focus of this review.

HSV-1 belongs to the alphaherpesvirus subfamily of the herpesviruses (67). It is a neurotropic virus that is highly prevalent among humans. HSV-1 can establish latent infection in the peripheral nervous system, allowing the virus to persist in the host causing life-long infection. HSV-1 infection can result in a number of symptoms ranging from the more common mucocutaneous lesions to more severe, life-threatening symptoms, including meningitis and encephalitis (14). Although the primary infection with HSV-1 may remain asymptomatic, it forms the starting point for the life-long recurrent episodes of symptomatic problems associated with the disease. Therefore, HS, as an entry coreceptor, has an important initial role in the patho-genesis of HSV-1.

Like other enveloped viruses, HSV-1 enters cells by inducing fusion between the viral envelope and host cell membrane. HSV-1 can enter host cells by two different pathways. First, HSV-1 can trigger fusion with the host cell plasma membrane at the cell surface. Second, the virus may enter into the cell through endocytosis using a phagocytosis-like uptake me-chanism and trigger fusion with the phagosomal membrane (11, 56). In either case the interaction with HS may be of critical significance. Initially, HS was found to be involved in viral binding during the attachment phase of HSV-1 entry (86). It was previously shown that soluble heparin, a molecule similar to HS, could bind to HSV-1 virions and inhibit their binding to host cells (54). Enzymatic removal of HS from the cell surface using heparinase led to significantly reduced binding of virions to cells and reduced infection of those cells (86). Cells defective in HS biosynthesis, but not chondroitin sulfate (CS) biosynthesis, are infected at a significantly reduced level (30, 65). Significance of HS in viral binding can also be demonstrated by a low speed centrifugation technique called spinoculation (64). HSV-1 entry into mutant cells defective in HS biosynthesis can be restored to near wild-type levels by spinoculating the virus and the mutant cells together. Spinoculation provides a stronger force to facilitate the adherence of virus particles on the cell surface. The fact that entry can be restored to near wild-type levels by spino-culation suggests strongly that initial interactions with HS may not be essential for entry provided an alternate mechanism can bring the virus in extreme close proximity with the plasma membrane (64).

The viral interaction with HS begins with the binding of HSV-1envelope glycoproteins gB and/or gC to HS moieties present on the cells surface (72). Next, a third HSV-1 envelope glycoprotein, gD, in-teracts with one of its receptors to trigger fusion with the host cell; a process that also requires gB, and two additional envelope glycoproteins, gH and gL. Though gC enhances viral binding via its interaction with HS, it is not essential for viral entry (71). The absence of gC results in reduced HSV-1 binding to the cell. However, virus that does bind can still infect the cell. In the absence of both gB and gC, binding is severely reduced, even compared to when only gC is absent, and the virus is also unable to mediate infection (25, 26). Soluble forms of both gB and gC, as well as, gB and gC extracted from virions, can bind both heparin and HS (26, 74, 81). Soluble gC is able to inhibit HSV-1 binding to cells (26, 73).

Specific amino acid resides from two separate regions of gC were determined to be critical for its interaction with HS (Arg-143, Arg-145, Arg-147, Thr-150 and Gly-247) (79). These arginine residues may interact with 6-O-and 2-O-sulfate groups found on HS and they may define the minimumrequirement to bind gC (18).This data correlates with a study that suggests basic and hydrophobicresidues localized at the Cys127–Cys144 loop of gC compose a major HS-binding domain (51).A short lysine-rich region of the gB sequence (residues 68-76) has been identified as the HS-binding domain of gB and is required for gB-mediated HSV-1 attachment (41). However, this region was not required for gB function during the fusion process of HSV-1 entry.

Attachment is not the only step in which HS is involved. HSV-1 gD can interact with three families of HSV-1 entry receptors to trigger fusion (7). These include: nectin-1 and nectin-2, which are both members of the immunoglobulin superfamily (20), herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) from the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family (53), and a specially modified form of HS known as 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate (3-OS HS) (66).

-

The final modification step during the biosynthesis of HS (summarized in Fig. 1) is the 3-O-sulfation of HS. Sulfate from PAPS (3x-phosphoadenosine 5x-phosphosulfate) is transferred to the 3-OH position of GlcN residues to form 3-OS HS (89). 3-O-sulfation is the final, and relatively rare, modification undergone by HS. Several proteins are able to selectively bind to the 3-OS HS motifs, including antithrombin, fibroblast growth factor 7, and, as mentioned earlier, HSV-1 gD (52, 66, 68, 69).

Figure 1. Biosynthesis of heparan sulfate. During its biosynthesis, HS has the potential to undergo a series of modifications. Above is a representative of a disaccharide unit consisting of a glucuronic acid (GlcA) and N-acetylated glucosamine (GlcNAc) residue. HS undergoes modifications in the following order: ⅰ.) N-deacetylation and N-sulfation of GlcNAc occurs, converting it to N-sulfoglucosamine (GlcNS), ⅱ.) C5 epimerization of GlcA to IdoA, ⅲ.) 2-O-sulfation of IdoA and GlcA, ⅳ.) 6-O-sulfation of GlcNAc and GlcNS units, ⅴ.) 3-O-sulfation of GlcN residues.

3-O-sulfation is carried out by a family of enzymes called 3-O-sulfotransferases (3-OSTs). Currently, seven members of the family have been identified: 3-OST-1, -2, -3A, -3B, -4, -5, -6 (58, 76, 87, 89). 3-OST-3A and 3-OST-3B have nearly identical amino acid sequences in the sulfotransferase domain and generate the same 3-O-sulfated disaccharides (47, 68). 3-OSTs consist of a divergent N-terminal domain and a C-terminal sulfotransferase domain that is conserved among all isoforms (68). The sulfotransferase domain determines the sequence specificity of each isoform (68, 90). The various isoforms are able to recognize unique saccharide sequences around the modification site (47, 68). This site-specific function of each isoform allows them to generate their own distinct 3-O-sulfated motifs. Thus, each isoform is able to produce a unique 3-OS HS chain with its own distinct function. For example, HS modified by 3-OST-1 contains anti-thrombin binding sites, while, HS modified by 3-OST-2, 3-OST-3, 3-OST-4, and 3-OST-6 interacts with HSV-1 gD and serves as an entry receptor for HSV-1 (58, 66, 76, 89). Interestingly, HS modified by 3-OST-5 has both anticoagulant activity and binds HSV-1 gD (87). The site specific function of these enzymes, along with their distinct expression pattern in cells and tissue, makes them key regulators of HS function (68).

-

The first 3-OST enzyme shown to be capable of binding HSV-1 gD and serving as an entry receptor for HSV was 3-OST-3 (66). Since then, all of the other known 3-OST enzymes have been studied for their ability to do the same. All of the enzymes, except 3-OST-1, have been shown to interact with gD and allow HSV-1 entry (58, 66, 76, 87, 89). Visual evidence has shown colocalization of 3-OS HS and HSV-1 gD during the fusion process (78). Soluble 3-OS HS was used to show that 3-OS HS was required to trigger the fusion process during HSV-1 infection, and not just required to anchor HSV-1 to specific locations on the cell surface (75-76). A similar study was performed using soluble formsof nectin-1 and nectin-2 to trigger entry into HSV-resistant cells (38). Soluble 3-OS HS, modified by 3-OST-3, functioned in a manner similar to that of the soluble nectins as it was also able to trigger entry in HSV-resistant cells (77). Cells deficient in glycosaminoglycan synthesis became susceptible to HSV-1 entry when spinoculated in the presence of 3-OS HS, further supporting the role of 3-OS HS in HSV-1 mediated fusion rather than cell attachment (77).

Besides entry, soluble 3-OS HS can also trigger cell-cell fusion (78). After entry occurs, the virus is able to spread throughout the host by a process known as cell-cell fusion. During this process, HSV-1 infected cells express the viral envelope glycoproteins required for fusion on their surface, allowing the infected cell to bind and fuse with neighboring uninfected cells. This results in the formation of large multinucleated cells called polykaryocytes or syncytia. While soluble 3-OS HS generated by 3-OST-3 can trigger cell-cell polykaryocytes fusion, 3-OS HS generated by 3-OST-1 cannot trigger entry or cell-cell fusion. HSV-1 is able to produce polykaryocytes during HSV-1 cell-cell fusion in cultured human corneal fibroblasts (CF) using 3-OS HS (78). Polykaryocyte formation depended heavily on the expression of 3-OS HS on the receptor expressing target CF cells, but not on the HSV-1 glycoprotein expressing effector cells. Interestingly, while 3-OS HS was able to trigger cell-cell fusion, previous studies have demonstrated that unmodified HS is not required for cell-cell fusion to occur (59).

Studies have tried to determine the specific saccharide structure in 3-OS HS that allows it to bind HSV-1 gD. A study looking at the crystal structure of the HSV-1 gD-HVEM complex predicted two possible 3-OS HS binding sites on gD (8). One binding site is a deep surface pocket that is positively charged, and the second binding site is a relatively flat surface that contains numerous basic amino acid residues. It was suggested the interaction between the positively charged amino acid residues from gD and the negatively charged sulfate groups from 3-OS HS might provide the electrostatic interactions to create binding sites for 3-OS HS. An octasaccharide deve-loped from HS modified by 3-OST-3 is able to bind gD (46). Amino acid mutations in the N-terminal region of gD that had a negative effect on its ability to interact with 3-OS HS are consistent with the proposed 3-OS HS gD-binding sites (92).

-

Besides HSV-1, many, but not all, members of the herpesvirus family interact with HS during infection. These include members of the alphaherpesviruses: HSV-2, varicella zoster virus (VZV), pseudorabies virus (PRV), andbovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1). It also includes members of the beta herpesviruses: human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and human herpes-virus 7 (HHV-7), and members of the gamma herpes-viruses: BHV-4 and Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV or HHV-8) (1, 12, 31, 44, 55, 67, 70, 80, 84, 86).

Though HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection share several similarities, they do exhibit some key type-specific differences in regards to their interaction with HS. Though both interact with HS, the relative importance of their HS binding glycoproteins differs. While gC plays a key role in attachment during HSV-1 entry, HSV-2 gC is not as important for this process (28, 81). HSV-2 gB is believed to play a much more critical role in attachment than HSV-1 gB (28). Difference in gC function is thought to be responsible for several differences in the biological activities of HSV-1 and HSV-2, such as affinity for cell surface HS (81), differential binding to the C3b component of complement (19), and differences in sensitivity to polyanionic and polycationic substances (27, 39, 40). Another key difference between these viruses is their affinity for 3-OS HS. Only HSV-1 gD, and not HSV-2 gD, interacts with 3-OS HS to trigger viral entry (66).

Like HSV-1 and HSV-2, other herpesviruses use specific viral envelope glycoproteins to bind to HS during the entry process. HCMV glycoproteins gM and gB interactwith HS to mediate entry into cells by attaching thevirion to the cell surface (12, 55). Studies using solubleheparin and the enzymaticremoval of HS have shown that KSHV also interacts with HS during entry and that interaction is critical for infection (1). Findings havesuggested that KSHV gpK8.1A is the glycoprotein that specifically binds to HS to mediate attachment (85). Still, only HSV-1 has been shown to use 3-OS HS as an entry receptor.

-

The most effective and widely used treatment for HSV infection currently is acyclovir (6). However, acyclovir is not always well tolerated and drug-resistant HSV-1 strains are rapidly emerging, especially in immunocompromised individuals (4, 16). Thus, the need for novel antiherpetic drugs is required. Due to its involvement in both attachment and entry of HSV-1 into host cells, HS has been a prime candidate for the development of therapeutic agents to inhibit HSV infection. These agents might also have the ability to inhibit the infection of other viruses that interact with HS. Multiple approaches involving HS are being developed to inhibit HSV-1 infection using both naturally occurring and synthesized molecules. While some highly cationic molecules are being synthesized to bind HS to inhibit HSV-1 binding and infection (33, 82), other molecules are being studied that can mimic HS.

One approach has been to identify other sulfated polysaccharides that can be used to inhibit HSV-1 infection. The idea was that these sulfated polysac-charides could mimic HS because of their similarity in structure and compete with it for the virus to inhibit infection. Numerous sulfated molecules have been explored, most notably, heparin and chemically modified derivatives of heparin (18, 23, 48). Other sulfated polysaccharides shown to inhibit HSV entry include pentosan polysulfate (24), dextran sulfate (15, 24), sulfated maltoheptaose (24), sulfated fucoidans (42, 60, 61), spirulan (22), and a low molecular weight molecule PI-88 which can inhibit entry and cell-cell spread (57).

Other studies have instead looked at the ability of sulfated nonpolysaccharide compounds to inhibit HSV infection because they are relatively easy to synthesize. Recently, it was discovered that a sulfated derivative of lignin could inhibit HSV infection (62). Lignin was able to mimic HS to inhibit infection. Inhibition of HSV-1 infection was dependent on the molecular weight of lignin with the heaviest chain being able to inhibit infection the best.

Several natural antimicrobial proteins and peptides have been studied for their ability to block viral entry or inhibit later stages of viral growth to inhibit infection (35). Lactoferrin and lactoferricin have been studied extensively for their antiherpetic ability. Lactoferrin (Lf) is a multifunctional iron-binding protein that is a component of the innate immune system and has antimicrobial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory activities (32, 43). Lf has anti-HSV activity and can inhibit HSV-1 infection (21, 49). Metal complexes of bovine Lf inhibit in vitro replication of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 (50). Recently, it was shown that one of the mechanisms of anti HSV-1 activity of Lf is its ability to compete with HSV-1 for binding to HS and CS (3, 32). Both bovine and human Lf can also inhibit cell-to-cell spread of HSV-1 and HSV-2 (36).

Lactoferricin (Lfcin) is a peptide generated by pepsin cleavage from the N-terminal part of Lf (21, 49). Both bovine and human Lfcin have been shown to exert antiviral activity against HSV-1 and HSV-2 (2, 3, 34). Like Lf, Lfcin also competes with HSV-1 for HS to inhibit infection (3). Lfcin can exhibit antiviral activity both at the cell surface and at later stages after internalization. Bovine and human Lfcin can inhibit cell-to-cell spread of HSV-1, but not HSV-2 (36).

A relatively new approach has been to use HS biosynthetic enzymes to develop biologically active polysaccharides and oligosaccharides (9, 13, 88). Recently, a 3-O-sulfated octasaccharide was synthesized, which is able to mimic the active domain of 3-OS HS (13). The 3-O-sulfated octasaccharide was synthesized by incubating a heparin octasaccharide (3-OH octasac-charide) with 3-OST-3. The results showed the 3-O-sulfated octasaccharide was able to more effi-ciently block HSV-1 infection than the heparin octasaccharide, suggesting it may be able to inhibit both attachment and fusion. The results suggest it is possible to inhibit HSV-1 entry using specific HS based oligosaccharides.

In summary, significant new and old information strongly implicate HS as an important co-receptor in HSV-1 entry into cells in particular and herpesvirus entry in general. Due to complexities involved in understanding HS structure it is difficult to speci-fically identify structural features of HS needed for viral interactions. However, the discovery of 3-OS HS and its association with the viral fusion mechanism has uncovered a strong new possibility that specificity within HS chains may be crucial for its function as a pathogen receptor (66, 78). More structural analysis will be needed to properly understand the true significance of HS in the entry process. Likewise, significant new work will be needed to establish the importance of HS in vivo. At present, virtually no information is available on its significance as a pathogen receptor in vivo.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: