HTML

-

In March 2013, the first 3 cases of severe disease due to a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus were detected in the Chinese provinces of Shanghai and Anhui (Gao R, et al., 2013). A total of 339 laboratory-confirmed cases with 100 deaths were reported until January 14, 2014 (WHO, 2014). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that human infection with the avian influenza A H7N9 subtype has been detected. Prior to this, the few influenza A (H7) human infections that have occurred have generally resulted in mild illness and conjunctivitis, with only one reported death (Fouchier R A, et al., 2004; Tweed S A, et al., 2004). Although some biological features are known and initial studies focused on pathogenesis have been performed (Zhou J, et al., 2013; Shen Z, et al., 2014; Belser J A, et al., 2013), several characteristics of this novel virus need to be revealed.

Influenza A virus is a member of the family Orthomyxoviridae. It contains a genome consisting of 8 RNA negative segments, which form 8 distinct ribonucleoprotein complexes with the viral nucleoprotein. The H7N9 viral genome was demonstrated to be a novel reassortant avian-originated virus, containing genes from different avian influenza types as follows: hemagglutinin (HA) of H7N3, neuraminidase (NA) of H7N9, and 6 internal genes from H9N2 (Gao R, et al., 2013; Liu D, et al., 2013). The human H7 virus has significantly higher affinity for human-like receptors (α-2, 6-linked sialic acid analogues) compared with avian H7, while retaining strong binding to avian-like receptors (α-2, 3-linked sialic acid analogues) characteristic of avian viruses (Xiong X, et al., 2013).

The clinical characteristics of H7N9 infection have been described (Gao H N, et al., 2013). Notably, H7N9 virus infection causes severe illness, including rapidly progressive pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which was characterized by bilateral ground-glass opacities and consolidation. These characteristics were accompanied by a high mortality rate, although currently, there are no pathological studies available on fatal cases. However, an ex vivo study showed that the viral antigen was detected in the epithelium of bronchus and lung tissues, as well as in type Ⅱ pneumocytes (Zhou J, et al., 2013). Although H7N9 causes such severe illness in humans, it is unclear as to why this is the case considering the virus contains the molecular features of a minimally pathogenic avian influenza virus (Gao R, et al., 2013; Liu D, et al., 2013). However, the ultrastructural features of the virus remain unknown and their elucidation may provide insight into its pathogenesis.

In this study, we examined the ultrastructure of the novel H7N9 avian virus isolates that caused human infection in China in 2013. Viruses isolated from chicken embryo allantoic cavity fluid were absorbed on a grid coated with formvar and carbon films, followed by negative staining with 1% phosphotungstic acid (pH 6.8) and air drying. Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells and human lung tissue explants were infected with virus in order to examine the ultrastructural and morphogenic characteristics of viral replication. Cells and tissue explants were infected with H7N9 virus (A/Anhui/1/2013, AH1) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 or 107 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50), respectively, for 24 h. Infected MDCK cell pellets and lung tissue blocks were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde/2.5% glutaraldehyde (0.1 mol/L cacodylate-buffered, pH 7.2) and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (0.1 mol/L cacodylate-buffered, pH 7.2), dehydrated with a graded ethanol series, and embedded in Spurr's low viscosity epoxy resin (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA, USA). Negativelystained samples and ultrathin sections of cell pellets and tissues were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and observed under a Tecnai12 transmission electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands).

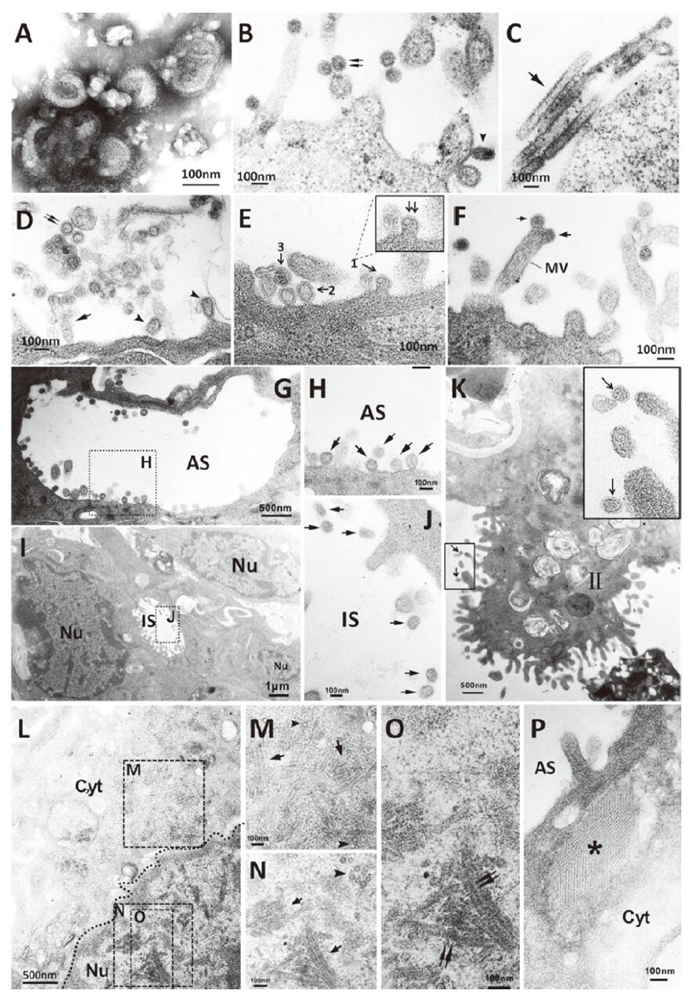

The results showed that most negatively-stained H7N9 virus particles presented as spherical (average diameter 113 nm) or ovoid with projections (average length 10 nm) of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase glycoproteins surrounding the periphery (Figure 1, panel A). Similarly, ultrathin section electron microscopy of H7N9-infected MDCK cells and human lung explants revealed that most extracellular virus particles were spherical or ovoid with an average diameter of 99 nm (Figure 1, panels B, D) with surrounding glycoprotein spikes. Only a small number of extracellular virus particles were filamentous (up to 730 nm in length) (Figure 1, panels C, D).

Figure 1. Morpholgical feature (A-D) and morphogenesis (E-P) of H7N9 avian influenza virus. A: Negatively stained virions grown in chicken eggs showing spherical or ovoid particles with distinct surface spikes; B-C: Spherical (double arrow), ovoid (arrowhead) or filamentous (arrow) virus particles with prominent projections grown in MDCK cells; D: Spherical (double arrow), ovoid (arrowhead) or filamentous (arrow) virus particles with prominent projections grown in human lung explants. E: Virus particles budding at an early stage (1), budding at a later stage (2) from human lung explants cell surface and extracellular viral particles (3); F: Virus particles budding from microvilli of human lung explant cell (arrow); G-H: Budding or released virus particles in alveolar space (arrow); I-J: Virus particles located in human lung explant intercellular space (arrow); K: Virus particles on type Ⅱ pneumocytes (arrow); L: Numerous tubular structures and dense rod-like structures present in H7N9 virus-infected pneumocytes each of which were of various lengths (tetragon). (Dashed line indicates nucleus border); M: Tubular structures with smooth outer edge (arrow) and cross-sections (arrowhead) in cytoplasm; N: Rod-like structures with a dense exterior (arrow) and cross-sections of tubules (arrowhead) in nulcleus; O: Rod-like structures with rough outer edges and striations perpendicular to the long axis in nulcleus (double arrow); P: Sieve-like structure (asterisk) in the cytoplasm of a pneumocyte. MV, microvilli; AS, alveolar space; IS, intercellular space; Ⅱ, type Ⅱ pneumocytes; Cyt, cytoplasm; Nu, nucleus.

Furthermore, we noted the presence of morphological features of infected cells that were similar to those previously described for influenza viruses. Upon sectioning the H7N9-infected human lung explants, budding virus particles were present on the plasma membrane at different stages(Figure 1, panel E). Viruses budding on the microvilli distal end were observed (Figure 1, panel F). In addition, viruses with dense-core granules or empty virus particles encircled by a thin layer of lipid membrane and spikes were detected. Virus particles were observed in the alveolar spaces, adjacent to the pneumocyte cell surfaces (Figure 1, panels G, H), and in pneumocyte intercellular spaces (Figure 1, panels I, J). Virus particles also localized on or close to the microvilli of type Ⅱ pneumocytes (Figure 1, panel K). Moreover, numerous tubular structures and dense rod-like structures of various lengths were observed in the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm of pneumocytes, respectively (Figure 1, panel L, M, N, O). The cytoplasmic tubular structures, which had a smooth outer edge, averaged 41 nm in diamete r(Figure 1, panel M), while the dense rod-like structures in the nucleus had rough outer edges which averaged 43 nm in diameter. These structures presented a regular dense striation perpendicular to the long axis with a central hole, as observed in longitudinal and transversal views, respectively (Figure 1, panels N, O). Furthermore, a sieve-like structure made up with a regular array of fibers (average 8 nm in diameter)was observed in the cytoplasm of a pneumocyte (Figure 1, panel P).

The morphological and morphogenic analysis of H7N9 avian influenza virus isolates demonstrated that it is pleomorphic, which is similar to other members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. Influenza viruses freshly isolated from the field are generally predominantly filamentous, while laboratory-adapted viruses are usually spherical (Choppin P W, et al., 1960). Egg or tissue culture adaptation often result in the loss of the filamentous phenotype, and laboratory strains of influenza A virus usually display a "spherical phenotype." In this study, we observed that freshly isolated H7N9 virus presented mainly as spherical particles with a small number of filamentous features. Of note, previous studies indicated that the morphology of influenza virus is host cell-dependent (Roberts P C, et al., 1998) and that some laboratory-adapted strains [e.g., A/Udorn/72 (H3N2)] are also filamentous (Bourmakina S V, et al., 2003).

As is typical for influenza viruses, the H7N9 virion assembly and budding occur at the apical surface of infected cells (Nayak D P, et al., 2004). In addition, the H7N9 virions were shown to bud from the tips of cellular microvilli, similar to that previously described (Kolesnikova L, et al., 2013), and this may play a role in human-sourced transmission. Inclusion bodies consisting of dense tubular and sieve-like structures were seen in the nuclei or cytoplasm of some infected cells of human explant lung tissues, similar to those previously reported for other influenza A-infected cells (Goldsmith C S, et al., 2011; Josset L, et al., 2008). In this study, dense tubules with an average diameter of 41 nm were found in both the cytoplasm and nuclei of pneumocytes and a sieve-like structure was observed in the cytoplasm (Figure 1, panel L, M, N, O, P). In addition, a dense rodlike structure with a rough outer edge was seen in the nuclei of pneumocytes, which is similar to a previous report focused on the 2009 pdmH1N1 virus (Goldsmith C S, et al., 2011). Previously, the M protein has been identified as a component of influenza nuclear tubular inclusion (Goldsmith C S, et al., 2011). Although the biological function of the various structures in relation to the pathogenesis of this novel H7N9 virus will require further study, they may be related to functions such as excessive host immune-response. Along these lines, previous studies have shown that cytokine storms play a role in H5N1 infection or may enhance the spread of the virus in infected tissues (Otte A, et al., 2011; Lee SM, et al., 2009). Similar to H5N1 infections, a cytokine storm was also present in severe cases of H7N9 (Zhou J, et al., 2013). Thus, the formation of the structure observed in this study may be an accumulation of viral proteins, which may activate host response.

Another distinctive feature of the novel H7N9 avian influenza virus is infection of the lower respiratory tract, as evidenced by the presence of viral particles in the alveoli and on microvilli of type Ⅱ pneumocytes. Clinical investigations suggested that the novel H7N9 virus causes severe illness, including pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), with high rates of intensive care unit (ICU) admission and death (Gao H N, et al., 2013). Although no human autopsy results on individuals infected with H7N9 have been reported, such studies would be helpful to understand lower respiratory tract infection to determine whether there is obvious damage to the lungs and whether this could be the cause of the high mortality rate.

In conclusion, we examined the ultrastructural characterization of the H7N9 virus through electron microscopy, revealing that the H7N9 virus presents similar morphological features in infected cells to those previously described for influenza viruses. The distinguishing features of this virus include dense tubular structures and, also, a sieve-like structure in the cytoplasm and/or nuclei of pneumocytes. These findings lay the foundation to begin to understand the morphogenesis and pathogenesis of the H7N9 virus.

-

We thank Cynthia S. Goldsmith from the USA CDC Atlanta for kind suggestions on this study and editorial changes to the English of the manuscript.

This study was supported by an Emergency Research Project on human infection with avian influenza H7N9 virus from the National Ministry of Science and Technology(No. KJYJ-2013–01–01 to Dr. Shu), the National Basic Research Program (973) of China (grant No. 2011CB504704 to Dr. Shu), and China Mega-Project for Infectious Disease (2013ZX10004-101).

All the authors declare that they have no competing interest. All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory tissues were followed.

DownLoad:

DownLoad: