-

Agrawal AA, Salsi E, Chatrikhi R, Henderson S, Jenkins JL, Green MR, Ermolenko DN, Kielkopf CL. 2016. An extended U2AF(65)-RNA-binding domain recognizes the 3′ splice site signal. Nat Commun, 7:10950

doi: 10.1038/ncomms10950

-

Ajiro M, Zheng ZM. 2014. Oncogenes and RNA splicing of human tumor viruses. Emerg Microbes Infect 3:e63

-

Ajiro M, Zheng ZM. 2015a. E6^E7, a novel splice isoform protein of human papillomavirus 16, stabilizes viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins via HSP90 and GRP78. mBio 6:e02014-e02068

-

Ajiro M, Zheng ZM. 2015b. Vemurafenib-resistant BRAF selects alternative branch points different from its wild-type BRAF in intron 8 for RNA splicing. Cell Biosci, 5:70

doi: 10.1186/s13578-015-0061-7

-

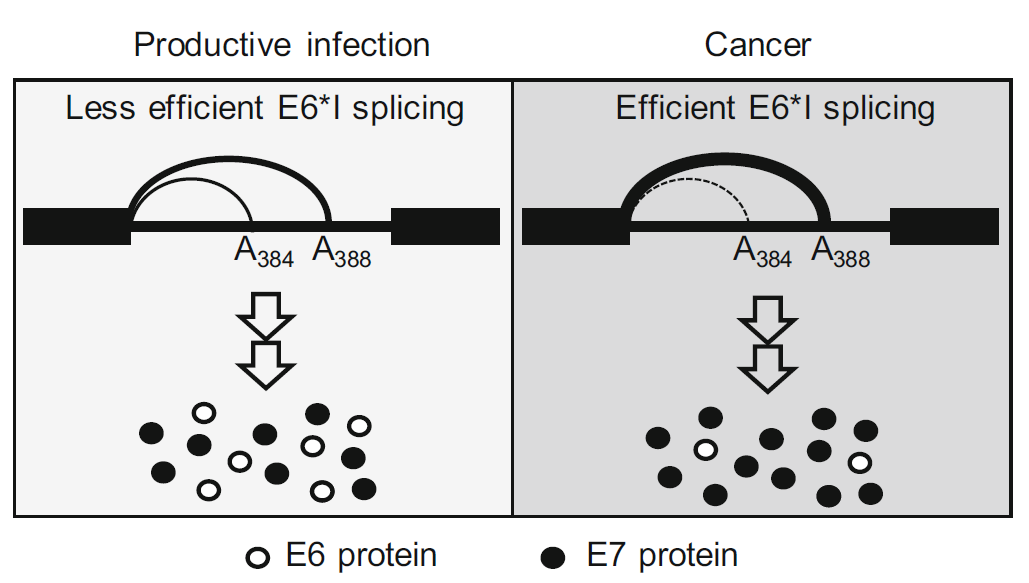

Ajiro M, Jia R, Zhang L, Liu X, Zheng ZM. 2012. Intron definition and a branch site adenosine at nt 385 control RNA splicing of HPV16 E6*I and E7 expression. PLoS ONE 7:e46412

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046412

-

Ajiro M, Jia R, Yang Y, Zhu J, Zheng ZM. 2016a. A genome landscape of SRSF3-regulated splicing events and gene expression in human osteosarcoma U2OS cells. Nucleic Acids Res, 44:1854-1870

doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1500

-

Ajiro M, Tang S, Doorbar J, Zheng ZM. 2016b. Serine/Arginine-rich splicing factor 3 and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 regulate alternative RNA splicing and gene expression of human papillomavirus 18 through two functionally distinguishable cis elements. J Virol, 90:9138-9152

doi: 10.1128/JVI.00965-16

-

Berglund JA, Abovich N, Rosbash M. 1998. A cooperative interaction between U2AF65 and mBBP/SF1 facilitates branchpoint region recognition. Genes Dev, 12:858-867

doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.858

-

Conklin JF, Goldman A, Lopez AJ. 2005. Stabilization and analysis of intron lariats in vivo. Methods San Diego Calif, 37:368-375

doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.08.002

-

de Villiers E-M. 2013. Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses. Virology, 445:2-10

doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.023

-

Desmet F-O, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Béroud G, Claustres M, Béroud C. 2009. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res 37:e67

doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215

-

Fay J, Kelehan P, Lambkin H, Schwartz S. 2009. Increased expression of cellular RNA-binding proteins in HPV-induced neoplasia and cervical cancer. J Med Virol, 81:897-907

doi: 10.1002/jmv.v81:5

-

Gao K, Masuda A, Matsuura T, Ohno K. 2008. Human branch point consensus sequence is yUnAy. Nucleic Acids Res, 36:2257-2267

doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn073

-

Kol G, Lev-Maor G, Ast G. 2005. Human-mouse comparative analysis reveals that branch-site plasticity contributes to splicing regulation. Hum Mol Genet, 14:1559-1568

doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi164

-

Lee Y, Rio DC. 2015. Mechanisms and regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem, 84:291-323

doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316

-

Mercer TR, Clark MB, Andersen SB, Brunck ME, Haerty W, Crawford J, Taft RJ, Nielsen LK, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. 2015. Genome-wide discovery of human splicing branchpoints. Genome Res, 25:290-303

doi: 10.1101/gr.182899.114

-

Mole S, McFarlane M, Chuen-Im T, Milligan SG, Millan D, Graham SV. 2009. RNA splicing factors regulated by HPV16 during cervical tumour progression. J Pathol, 219:383-391

doi: 10.1002/path.v219:3

-

Pineda JMB, Bradley RK. 2018. Most human introns are recognized via multiple and tissue-specific branchpoints. Genes Dev, 32:577-591

doi: 10.1101/gad.312058.118

-

Ranjeva SL, Baskerville EB, Dukic V, Villa LL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Giuliano AR, Dwyer G, Cobey S. 2017. Recurring infection with ecologically distinct HPV types can explain high prevalence and diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 114:13573-13578

doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714712114

-

Shi Y. 2017. Mechanistic insights into precursor messenger RNA splicing by the spliceosome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 18:655-670

doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.86

-

Sickmier EA, Frato KE, Shen H, Paranawithana SR, Green MR, Kielkopf CL. 2006. Structural basis for polypyrimidine tract recognition by the essential pre-mRNA splicing factor U2AF65. Mol Cell, 23:49-59

doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.025

-

Sohail M, Xie J. 2015. Diverse regulation of 3′ splice site usage. Cell Mol Life Sci, 72:4771-4793

doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2037-5

-

Sutandy FXR, Ebersberger S, Huang L, Busch A, Bach M, Kang HS, Fallmann J, Maticzka D, Backofen R, Stadler PF, Zarnack K, Sattler M, Legewie S, König J. 2018. In vitro iCLIP-based modeling uncovers how the splicing factor U2AF2 relies on regulation by cofactors. Genome Res, 28:699-713

doi: 10.1101/gr.229757.117

-

Suzuki H, Zuo Y, Wang J, Zhang MQ, Malhotra A, Mayeda A. 2006. Characterization of RNase R-digested cellular RNA source that consists of lariat and circular RNAs from pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res 34:e63

doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl151

-

Taggart AJ, DeSimone AM, Shih JS, Filloux ME, Fairbrother WG. 2012. Large-scale mapping of branchpoints in human pre-mRNA transcripts in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 19:719-721

doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2327

-

Tang S, Tao M, McCoy JP, Zheng ZM. 2006. The E7 oncoprotein is translated from spliced E6*I transcripts in high-risk human papillomavirus type 16- or type 18-positive cervical cancer cell lines via translation reinitiation. J Virol, 80:4249-4263

doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4249-4263.2006

-

Tavanez JP, Madl T, Kooshapur H, Sattler M, Valcárcel J. 2012. hnRNP A1 proofreads 3′ splice site recognition by U2AF. Mol Cell, 45:314-329

doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.033

-

Vogel J, Hess WR, Börner T. 1997. Precise branch point mapping and quantification of splicing intermediates. Nucleic Acids Res, 25:2030-2031

doi: 10.1093/nar/25.10.2030

-

Vousden KH. 1994. Interactions between papillomavirus proteins and tumor suppressor gene products. Adv Cancer Res, 64:1-24

doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)60833-7

-

Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. 1999. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol, 189:12-19

doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9896

-

Wang X, Meyers C, Wang HK, Chow LT, Zheng ZM. 2011. Construction of a Full Transcription Map of Human Papillomavirus Type 18 during Productive Viral Infection. J Virol, 85:8080-8092

doi: 10.1128/JVI.00670-11

-

Wang X, Liu H, Wang HK, Meyers C, Chow L, Zheng ZM. 2016. HPV18 DNA replication inactivates the early promoter P55 activity and prevents viral E6 expression. Virol Sin, 31:437-440

doi: 10.1007/s12250-016-3887-1

-

Will CL, Lührmann R. 2011. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3:a003707

-

Zamore PD, Patton JG, Green MR. 1992. Cloning and domain structure of the mammalian splicing factor U2AF. Nature, 355:609-614

doi: 10.1038/355609a0

-

Zheng ZM. 2004. Regulation of alternative RNA splicing by exon definition and exon sequences in viral and mammalian gene expression. J Biomed Sci, 11:278-294

doi: 10.1007/BF02254432

-

Zheng ZM. 2010. Viral oncogenes, noncoding RNAs, and RNA splicing in human tumor viruses. Int J Biol Sci, 6:730-755

-

Zheng ZM, Baker CC. 2000. Parameters that affect in vitro splicing of bovine papillomavirus type 1 late pre-mRNAs. J Virol Methods, 85:203-214

doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00172-X

-

Zheng ZM, Baker CC. 2006. Papillomavirus genome structure, expression, and post-transcriptional regulation. Front Biosci, 11:2286-2302

doi: 10.2741/1971

-

Zheng ZM, Reid ES, Baker CC. 2000. Utilization of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 late-stage-specific nucleotide 3605 3′ splice site is modulated by a novel exonic bipartite regulator but not by an intronic purine-rich element. J Virol, 74:10612-10622

doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.22.10612-10622.2000

-

Zheng ZM, Tao M, Yamanegi K, Bodaghi S, Xiao W. 2004. Splicing of a cap-proximal human Papillomavirus 16 E6E7 intron promotes E7 expression, but can be restrained by distance of the intron from its RNA 5′ cap. J Mol Biol, 337:1091-1108

doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.023

-

Zhuang YA, Goldstein AM, Weiner AM. 1989. UACUAAC is the preferred branch site for mammalian mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 86:2752-2756

doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2752

-

Zur Hausen H. 2002. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer 2:342-350

doi: 10.1038/nrc798